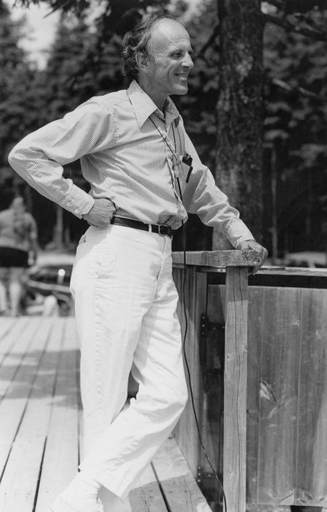

Paul Soldner, founding director at Anderson Ranch Paul Soldner, founding director at Anderson Ranch By James Baker Recently, Stuart Kestenbaum – long-time Haystack Mountain School of Crafts Director and more recently Artistic Director of the new Monson Arts Residency program – asked me to reflect on my time at Anderson Ranch Arts Center (Colorado, 1986-2006) and later at Pilchuck Glass School (Washington State, 2010-2018) and to address my life with craft-based education. Here are Stu’s questions and my answers: What changed in workshops during your long involvement (from Anderson Ranch to Pilchuck)? In my early years, looking in from the outside most workshop programs looked like “summer camp for adults” and therefore not taken very seriously. On the inside, often being small and working with few resources, these artist communities thought of themselves as alternatives to systems of higher education; more egalitarian and free-spirited and ambitiously taking risks. I remember a lot of time spent clarifying educational missions, refining programs and expanding facilities. In retrospect, these were start-up non-profit organizations going through a fairly normal maturation process; initially begun as experiments in learning and living often followed by rapid growth in attendance while not having enough financial security to ensure making it to the next season. Educationally, there was a bias toward developing students’ technique more than their vision. Again, as a generalization, these programs offered study in disciplines that were segregated from the mainstream art world; courses in ceramics, woodworking, glassmaking, textiles, book arts, printmaking and photography and very few if any painting and sculpture classes.Today, much has changed. Most organizations have developed a full roster of year-round workshop and residency programs – often running adjunct outreach programs directed toward underserved groups. They confidently articulate their missions and visions and consistently offer excellently planned and delivered programs balancing technical and conceptual skill development with the benefit of greater financial stability, a better-trained staff and more prepared, engaged and philanthropic boards. While there is sometimes expressed a wistful yearning for the more free-wheeling days, I’m fond of reminding anyone interested in listening that “the good old days are better now than they used to be!” What stayed the same? The supportive and explorative spirit of students and instructors is as high as its ever been and continuing a tradition of fostering life-long personal and professional relationships. The educational insights of the organizations’ founders and the quality of instruction they inspired – such as at Haystack Fran Merritt recognizing the need of aspiring artists to train with leaders in their fields through short-term workshops, Paul Soldner at Anderson Ranch developing an atmosphere of artists learning from each other “through osmosis” in a residency environment of mutual creativity and support and Dale Chihuly at Pilchuck engaging renowned artists from other fields and from around the world to experiment with glass and in so doing expanding the material’s aesthetic vocabulary – these educational innovations are examples of what fueled remarkably successful organizations led by artists for artists and increasingly supported by enlightened philanthropists who understand that one of the key pillars of a society’s artistic culture rests on a foundation of vibrant and robust artist communities. How does it feel to spending time on your own work now? Like many artists who work in and for nonprofit workshop and residency programs, personally I have thrived on the engagement, social relevance and, frankly, the stimulation and inspiration of an artist community as well as the open- ended freedom and time to pursue my own work. I can now see that at different stages in life the balance between the two ‘pulls’ means, in practice, committing more to one than the other. Through working in artist communities, I have gained so much clarity from being around, and serving, artists who have enormous experience at making their work. Right now taking those lessons and applying them to my own work – lessons centered on discipline, commitment, courage and purpose in one’s work – are helping me be more effective and more fulfilled in my own artistic practice.

0 Comments

Kathy & Nozumu Kathy & Nozumu

We believe that our programs help us understand what humankind has in common and that international exchanges are a great way to connect cultures through craft’s universal language of material, skill, and ingenuity. In 2017 we developed an exchange program with the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park in Japan. Last summer Nozumu Shinohara attended programs at Haystack and Penland. In December, American potter Kathy King spent a month in residence in Shigaraki.

Read more about her experience here:  King Work – brooch forms in progress and glazed King Work – brooch forms in progress and glazed

This year, I was fortunate enough to take part in an exchange program with Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park in Japan from November to December. My counterpart, Shigaraki potter, Nozumu Shinohara, had traveled to both Haystack and Penland last summer and came to visit me when I arrived.

I worked among nine different artists hailing from Japan, Taiwan, Sweden, Argentina and France of all different ages in a large, open studio space within the larger park. During my stay, two invited artists worked in an adjoining space, - sculptor Vilma Villaverde (http://vilmaceramista.wixsite.com/villaverde/about ) and painter Yoshitomo Nara (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshitomo_Nara) inspiring all as they worked on sculptures that would later be installed on-site. The park, features a spectacular tiered system of spaces carved into a hillside and has ample opportunity for one to “get their steps” in. During my visit, daily walks included observing noborigama and anagama kiln firings, strolling the paths flanked by numerous outdoor ceramic sculptures from past residents, viewing examples of area ceramic production in an exposition space as well as the on-site museum that featured an Imari ware exhibition. The view from the top often came with a view of wood-kilns firing from the numerous potteries that surround Shigaraki. The journey begins with a trip to the local clay supplier whereby the clays are unlike much of what we can access in the U.S. The area, known for its feldspathic rock-rich clay is ideal for making large sculpture with very low shrinkage rates. That speckling of rocks in the clay were not ideal for my own method of carving into clay (sgraffito) but the porcelain available was ideal. Rather than work in my standard black and white style, the clay was too beautiful to cover with slip and instead, I experimented with carving solely into the white surface. Still, the rate at which my studio-mate sculptors were able to build with local clays and the variety of colors available were remarkable! Residents also have access to excellent staff and a multitude of kiln firing choices from electric to gas and wood. An incredibly energy conscious studio, the kiln room featured a room of controllers that looked straight out of science fiction movie (only the staff allowed). In the evening the group would return to the adjoining housing with private dorm rooms/bath and, often times, gathered together in the communal kitchen/lounge to make dinner. Thankfully, resident artists such as Japanese sculptor Maria Murayama (http://www.maria-murayama.com/ ) would quickly reassign my duties to setting the table rather than assist in cooking one of the many amazing Japanese meals. Artists are responsible for their own food so on other days I would trek into town armed only with five basic Japanese phrases. Wishing I had spent the time to learn Kanji, the grocery store was a challenge and, much to my surprise, my first can of purchased tuna fish came with a vertebra in it! I soon became a repeat customer at the café located within the park featuring an inventive interpretation of pizza. When touring the local restaurants, stores and potteries, one will observe a multitude of Tanukis – a characterized Japanese raccoon dog sculpture sold throughout the area promising wealth and good luck to the owner. A stay in Shigaraki would be incomplete without a trip to the nearby Miho Museum (http://www.miho.or.jp/en/ ). This museum and its mountain top location is breathtaking – both for its amazing collection of ancient global art and ceramics but for its scenery. Near the end of my residency, I provided a slide show of my own work and apparently gave the translator quite a challenge with my narrative work. I called to the audience to ask if anyone had attended a craftschools.us (http://www.craftschools.us/) organization and was delighted to see how many international artists had and we took a group photo to celebrate our common love of the experience. In addition to being able to work in this amazing ceramic center, it was a gift to be able to live within a community that was so very kind and thoughtful. In Shigaraki, the pace is slower than ours and basic human interaction allows time for pleasantries and not as much time attached to a cell-phone – whether it be in the studio or the local store. Returned to my busy role at the Harvard Ceramics Program (https://ofa.fas.harvard.edu/ceramics ) , I look around at my own community craft space with a new appreciation – pleased to be part of an international conversation on the importance of craft education. I cherish my time at Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural park and thank craftschools.us for allowing me the opportunity of studio time, experimentation and growth in such an outstanding setting. Kathy King www.kathykingart.com

Jen Bervin’s interdisciplinary work often combines art, science and writing. One recent project is Silk Poems, a poem written nanoscale in the form of a silk biosensor in collaboration with Tufts University’s Silk Lab, and also published as a book. Another project, The Dickinson Composite Series, is a series of large-scale embroideries that depict the variant markings in Emily Dickinson’s original manuscripts. Her work as a poet and visual artist takes her in surprising directions. She says, “I love research because I don’t know what I’ll find.” Make/Time shares conversations about craft, inspiration, and the creative process. Listen to leading makers and thinkers talk about where they came from, what they're making, and where they're going next. Make/Time is hosted by Stuart Kestenbaum and is a project of craftschools.us. Major funding is provided by the Windgate Charitable Foundation. Our residential craft schools always have interesting and fun things happening. Check regularly to stay on board with current goings-on at your favorite craft school!

This fall: Penland in North Carolina is accepting applications for it's core fellowship program. Deadline is soon... October 15th! More info here. Rolling applications for one of the five Artists in Residence programs are open at Arrowmont! Every year, Pilchuck Glass School offers the John H. Hauberg residential fellowship program. Applications are due Oct. 26th! Peter's Valley had their amazing craft fair at the end of September, but there are some truly excellent opportunities for 2018, including a group trip to Cuba! See what they have coming up here.

The schools of the craftschool.us consortium (Arrowmont, Haystack, Penland, Peters Valley, and Pilchuck) want makers of all kinds to know about the dynamic educational experiences that take place in our workshops. We believe that our programs help us understand what humankind has in common and that international exchanges are a great way to connect cultures through craft’s universal language of material, skill, and ingenuity. This year we developed an exchange program with the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park in Japan..

Nozumu Shinohara, a potter who lives in Shigaraki, was selected to participate in a two-week residency program at Haystack followed by a two-week workshop at Penland. In the fall American potter Kathy King, director of education in the ceramics program at the Office for the Arts at Harvard University, will travel of Shigaraki for a month-long residency. Shigaraki potters are known for wood-firing and a rough clay body, and Kathy works in porcelain creating drawn narratives on her pots. She says that she is looking forward to working on a different surface and experimenting with other clays.  Lily Yeh is a co-founder of The Village of Arts and Humanities, for which she also has served as executive director and lead artist. Founded in 1986, the Philadelphia-based, non-profit organization aims to build community through art, learning, land transformation, and economic development. In 2002, Lily began Barefoot Artists, which continues her style of community building through art on an international level, in places such as Rwanda, Kenya, Ghana, Ecuador, and China. Lily Yeh seeks to build a more compassionate future through her collaborative work. She told the Christian Science Monitor, “I have found that the broken spaces are my living canvas. In our brokenness, our hearts reach for beauty.” Make/Time shares conversations about craft, inspiration, and the creative process. Listen to leading makers and thinkers talk about where they came from, what they're making, and where they're going next. Make/Time is hosted by Stuart Kestenbaum and is a project of craftschools.us. Major funding is provided by the Windgate Charitable Foundation. Don't forget! Registration is still open for many residential craft programs. Check out more and find your best match here!

The Make/Time podcasts from host Stu Kestenbaum are a great background to doing your favorite work. Hear from leading artists in the U.S. Craft world talk about craft, inspiration and the creative process.

|

Archives

August 2018

Visit a Craft School!

|